Mexico’s Mass Disappearances and the Drug War (Ayotzinapa: The Missing 43 Students) : Home

- Home

- Drug War Toggle Dropdown

- Teacher Training Schools and Guerrilla Movements in Guerrero, Mexico Toggle Dropdown

- A y o t z i n a p a Toggle Dropdown

- Ephemera Collection Toggle Dropdown

- Human Right Violations Related to the Drug War Toggle Dropdown

Credits

This Research Guide was created by Edith Beltrán Mínehan with guidance from Paloma Celis-Carbajal and support from the Latin American, Caribbean and Iberian Studies Program (LACIS).

Partial funding from the International and Foreign Language Education of the U.S. Department of Education, Title VI of the Higher Education Act, National Resource Center program.

Subject Librarian

What is This Reseach Guide?

This research guide was created after the exhibition Ayotzinapa: We Will Not Wither, held at Memorial Library from September 16 to October 30, 2015.

It is intended to be an introduction to the topic & library resources regarding the disappearance of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, México.

It contains resources for:

- Instructors,

- Graduate students, and

- Undergraduate students.

Please note that it is selective in nature and not intended to be a comprehensive list on the subject.

This guide includes:

- Resources found at University of Wisconsin - Madison Libraries,

- Information about the Ayotzinapa Collection of Ephemera which holds posters, handouts, booklets, etc. collected at the marches in Mexico during 2014.

- Information about how to access both print and electronic resources about the Drug War, Ayotzinapa, the Rural Teachers' Colleges in Mexico, and Human Rights Violations in Mexico.

- Relevant Links to Internet Resources.

Ayotzinapa, A Burning Wound

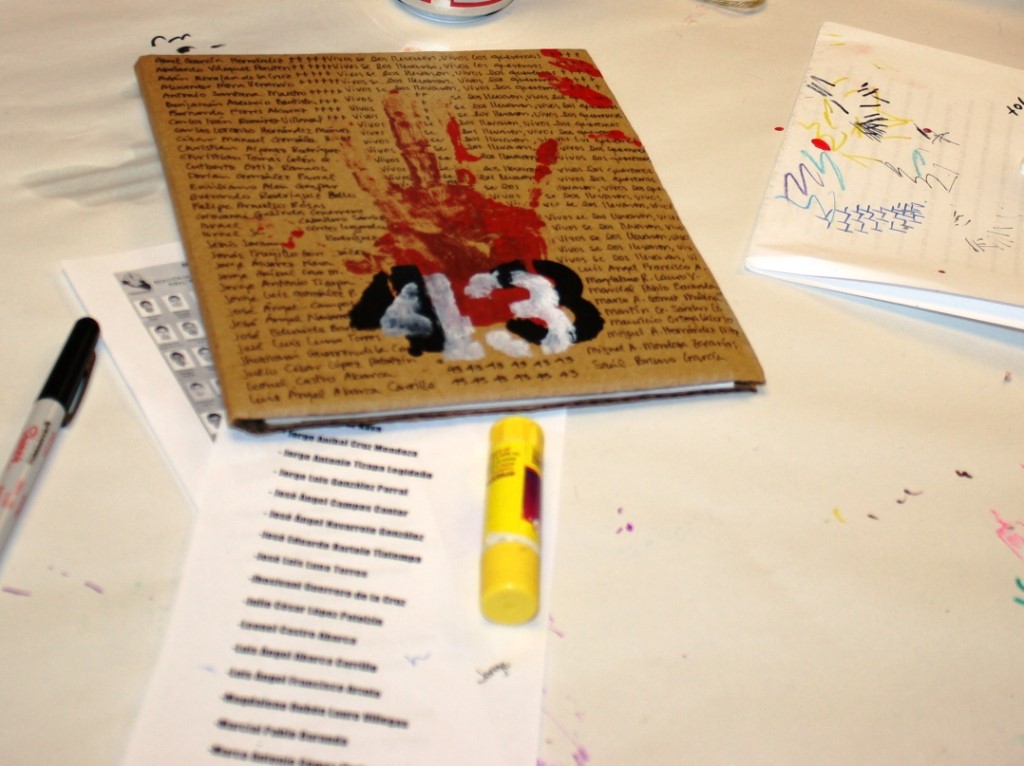

Prologue to Ayotzinapa: Forced Dissapearances. Madison: Pensaré Cartonera/Axolote, 2015. Print. This item is held at UW-Madison Special Collections.

On September 26, 2014, Mexican society learned to count their dead. Before that day, deaths were never counted, perhaps because being murdered was an everyday occurrence, or perhaps because fear petrified people’s hearts. Conventional wisdom claimed it was better not to know; certainty was a source of danger. The elders believed it was necessary to let the dead bury their own dead. It is presumed that a million people perished during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). There were more than 75,000 casualties during the Cristero War (1926-1929). It is supposed that there were 300 deaths at the massacre of Tlatelolco (1968), and roughly 3000 deaths and disappearances during the Dirty War (1964-1982). Estimates indicate that since the drug war’s inception (2006-2015) 145,000 civilians have been killed or disappeared. However, we know for sure that on September 26, 2014 six people were killed in Iguala, Guerrero—one of them skinned—and 43 students of the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa were detained/disappeared by the municipal police with an allegedly concerted effort with the Guerrero Unidos cartel, and with the acquiescence of the 57th Infantry Battalion of the Mexican army.

On September 26, 2014, Mexican society learned to count their dead. Before that day, deaths were never counted, perhaps because being murdered was an everyday occurrence, or perhaps because fear petrified people’s hearts. Conventional wisdom claimed it was better not to know; certainty was a source of danger. The elders believed it was necessary to let the dead bury their own dead. It is presumed that a million people perished during the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). There were more than 75,000 casualties during the Cristero War (1926-1929). It is supposed that there were 300 deaths at the massacre of Tlatelolco (1968), and roughly 3000 deaths and disappearances during the Dirty War (1964-1982). Estimates indicate that since the drug war’s inception (2006-2015) 145,000 civilians have been killed or disappeared. However, we know for sure that on September 26, 2014 six people were killed in Iguala, Guerrero—one of them skinned—and 43 students of the Normal Rural School of Ayotzinapa were detained/disappeared by the municipal police with an allegedly concerted effort with the Guerrero Unidos cartel, and with the acquiescence of the 57th Infantry Battalion of the Mexican army.

Academics, journalists, and human rights defenders had already begun counting the barbaric manners in which people were being murdered because of the War on Drugs. Overnight on the thoroughfare corpses turn up beheaded, dismembered, hanging on bridges, locked in car trunks, covered with blankets, or simply shot. Some others are buried in clandestine graves or dissolved in acid. Those who have been following the human rights situation in Mexico were certain Iguala’s egregious crime would go unnoticed, just as what happened when 340 bodies were found in mass graves in the state of Durango in 2012, or that the crime’s effects would be downplayed as so many atrocities have been in which the state has been responsible. However, Iguala has fostered a domestic and international resonance unprecedented in Mexican history. How is it that in a country were so much blood is being spilled 43 students became the symbol of the savagery that is the War on Drugs? Public impatience ultimately dwindled after authorities continuously distorted reports. The incompetence of Mexican authorities, however, does not explain the reasons why millions of people felt challenged by the Ayotzinapa case. The students came from rural campesino backgrounds, they were inhabitants of the poorest and most violent state in Mexico, and victimized for being activists, despite not breaking any law. As a result, they revived the never-healed wound of the 1968 student massacre. Once again the public force that should protect citizens ruthlessly attacked a group of unarmed idealist youths. 1968 and 2014 are scorch marks of State crimes.

The social movement that flourished after Iguala unanimously claims: “The State did it!” because historical memory proves that only the State has capabilities of performing massive atrocities. Yes, the State kills, tortures, kidnaps, forcibly disappears, and never apologizes. The same State that abducted 43 students and thousands more has taken away joy, hope, dignity, and the right to a promising future from the Mexican people. This book is about the outcry of a torn and angry society. “The 43” have become the symbol of murdered innocence. Mexicans no longer trust their government or its institutions, and have taken to the streets shouting: “They have taken so much from us, they even took our fear!” May this anger and the immense pain created by the burning wound that is Ayotzinapa no longer makes us indifferent.

-

Ayotzinapa: forced disappearances

This item is held at Special Collections.

Bilingual edition. [Valencia, Spain] : Pensaré Cartoneras ; [Madison, Wisconsin] : Axolote ; [2015] [Madison, Wisconsin] : Axolote

Call Number: CA 16662y no. 15

Ayotzinapa: forced disappearances

This item is held at Special Collections.

Bilingual edition. [Valencia, Spain] : Pensaré Cartoneras ; [Madison, Wisconsin] : Axolote ; [2015] [Madison, Wisconsin] : Axolote

Call Number: CA 16662y no. 15

Need to cite articles, books, or Web pages?

Citing Sources - resources and examples of citation styles

UW-Madison Writing Center's Writer's Handbook has tips on citation styles (APA, Chicago, CBE, MLA, etc.).

Information on how to avoid plagiarism from UW-Madison's Writing Center.

Use citation managers to organize your references and create bibliographies.